Hardships when Building without the Standard Library

Recently, I have managed to display a magnificent

magenta screen

using OpenGL.

In order to learn every detail that goes into getting a window with

OpenGL rendering running, I tend to avoid any external libraries.

This includes the C++ standard library.

Among some known pitfalls when building without the standard library,

the first major road block that I encountered was the

sin

function that comes up often during rendering, e.g. to represent rotations.

On my way to get a working sin function, I encountered some

hardships when building without the C++ standard library.

Note: Currently, I build my software on Windows using Microsoft Visual C++ (MSVC).

The Setup

In order to build without the C++ standard library, you have to use the

/NODEFAULTLIB

linker option (Linker → Input → Ignore all default libraries).

You can no longer implement your

WinMain

function,

since it is normally called by the C runtime, which is no longer present.

If you use the windows subsytem, i.e. /SUBSYSTEM:WINDOWS,

the startup function is now called WinMainCRTStartup by default.

But you can set your own name via the

/ENTRY linker option.

Common Pitfalls

There are some pitfalls when building without the standard library that I was aware of before embarking on this endeavor. You have to manually do tasks that have been handled by the C runtime before.

Exit your Process

Simply returning from WinMainCRTStartup will leave your process running,

presumbly just idling along.

You have to make sure to call

ExitProcess at the end of your program.

extern "C" int WINAPI WinMainCRTStartup(void) {

int exitCode = mainFunction();

// We have to manually exit the process since we do not use the C Standard Library

ExitProcess(exitCode);

}

Global Initializers do not Run

Global variables can be initialized by constants. But, code that initializes global variables will not run:

int f() { return 9000; }

int global_a = 8000; // Will be set to 8000

int global_b = f(); // Will not be initialized, i.e. set 0

Initializers Might Use memset

You might have big structures or arrays in your code that you want to initialize. For example a buffer to hold the info log from OpenGL:

int success = 0;

glGetShaderiv(shader, GL_COMPILE_STATUS, &success);

if (!success) {

// Initialize all the elements of the infoLog array to zero

char infoLog[512] = {};

glGetShaderInfoLog(shader, sizeof(infoLog), nullptr, infoLog);

// Output the info log

}

The compiler might output a call to

memset

to initialize of infoLog variable.

Whether the compiler does this, depends on your other compiler settings.

I found that in release mode, it was more likely to memset than in debug mode.

But your mileage may vary.

Also, the

/Oi compiler flag seems to have some influence.

Nevertheless, if the compiler inserts a call to memset,

you will see following linker error:

error LNK2019: unresolved external symbol memset referenced in function

"void __cdecl gl_compileShader(unsigned int,char const *)" (?gl_compileShader@@YAXIPEBD@Z)

fatal error LNK1120: 1 unresolved externals

In order to fix this, you have to provide your own implementation of memset.

The naive approach will lead to another error, since the compiler might consider

memset to be an intrinsic that cannot be implemented directly.

error C2169: 'memset': intrinsic function, cannot be defined

Therefore, you should mark memset as a

normal function via

#pragma function

before implementing it:

// Mark memset as function so that we can implement it

#pragma function(memset)

void* __cdecl memset(void* destination, int value, size_t size) {

// You should probably look a more optimized version of memset

char* dest = (char*)destination;

for (int i = 0; i < size; ++i) {

dest[i] = value;

}

return dest;

}

Floating Point Arithmetic Requires Setup

If you use floating point numbers, i.e. float or double

variables and computations, you will get the following linker error:

error LNK2001: unresolved external symbol _fltused

fatal error LNK1120: 1 unresolved externals

The _fltused variable seems to have originated from the old days

where we still needed floating point emulation libraries.

These were necessary if the CPU did not support floating point instructions.

You can read Raymond Chen's article about

Understanding the classical model for linking for details.

Since nowadays all CPUs support floating point instructions,

this is just a remnant of the past.

We can replace it by a simple mock to satisfy the linker:

// This variable is expected by the linker if floats or doubles are used

extern "C" int _fltused = 0;

Getting on the Same Wave Length

Now that we have a program that compiles, links and runs without the standard library,

we can focus on the main antogonist of this article: The sin function.

Let's try calling the sin function results from math.h:

#include <math.h>

int f() {

double a = sin(0.0);

}

As expected this yields the following linker error:

error LNK2019: unresolved external symbol sin referenced in function "int __cdecl f(void)"

Intrinsics to the Rescue?

Remember the /Oi compiler flag to enable intrinsic functions?

Maybe it can help us by inlining the sin function.

If we look at the

MSVC intrinsics table, we can see that sin has an intrinsic form

on all architectures.

So let's enable /Oi and ... nothing changes.

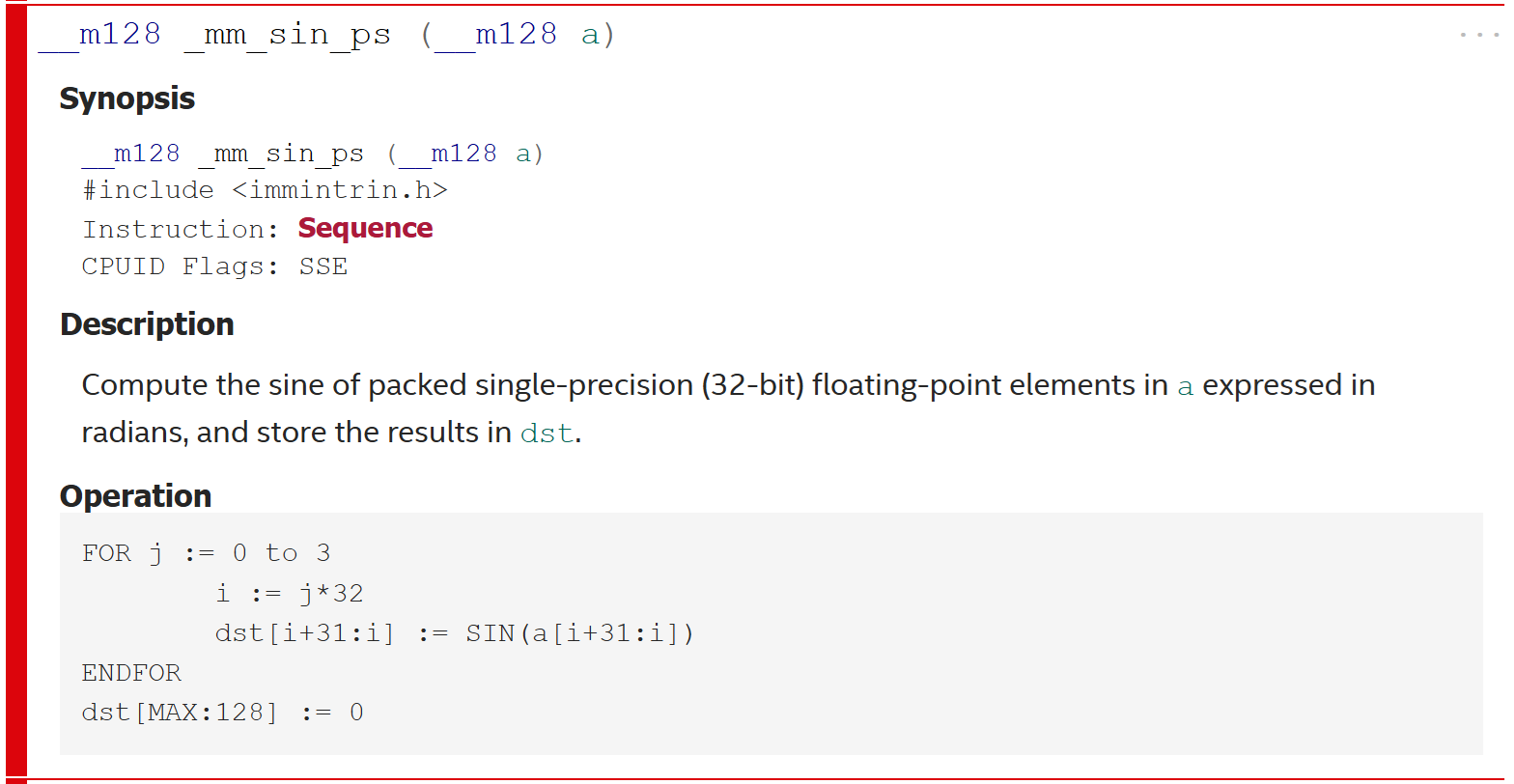

Another intrinsic we might consider is

_mm_sin_ps from the

SSE instruction set.

It actually calculates the sin for multiple values at a time.

But we can just extract a single value later:

#include <immintrin.h>

float sin(float x) {

__m128 x4 = _mm_set1_ps(x); // Put x into all four lanes

__m128 y4 = _mm_sin_ps(x4); // Calculate sin(x) for all lanes

return *(float*)&y4; // Extract the first lane

}

Let's give it a try and see:

error LNK2019: unresolved external symbol __vdecl_sinf4 referenced in function

"float __cdecl sin(float)" (?sin@@YAMM@Z)

fatal error LNK1120: 1 unresolved externals

What is this weird function __vdecl_sinf4?

It seems that although we are using the intrinsics directly,

the compiler still inserted a function call into another library.

If we link against the standard library, we can inspect the

generated assembly to see the call:

float sin(float x) {

00007FF681A634A0 vmovss dword ptr [rsp+8],xmm0

00007FF681A634A6 sub rsp,68h

__m128 x4 = _mm_set1_ps(x); // Put x into all four lanes

00007FF681A634AA vmovss xmm0,dword ptr [x]

00007FF681A634B0 vbroadcastss xmm0,xmm0

00007FF681A634B5 vmovups xmmword ptr [rsp+20h],xmm0

00007FF681A634BB vmovups xmm0,xmmword ptr [rsp+20h]

00007FF681A634C1 vmovups xmmword ptr [x4],xmm0

__m128 y4 = _mm_sin_ps(x4); // Calculate sin(x) for all lanes

00007FF681A634C7 vmovups xmm0,xmmword ptr [x4]

00007FF681A634CD call __vdecl_sinf4 (07FF681A64720h)

00007FF681A634D2 vmovups xmmword ptr [rsp+40h],xmm0

00007FF681A634D8 vmovups xmm0,xmmword ptr [rsp+40h]

00007FF681A634DE vmovups xmmword ptr [y4],xmm0

return *(float*)&y4; // Extract the first lane

00007FF681A634E4 vmovss xmm0,dword ptr [y4]

}

We can clearly see, that the code is calling into the function

__vdecl_sinf4.

If we try to debug into the function,

the debugger tries to open a file named svml_ssinf4_dispatch.asm.

That might give us a hint of what is going on.

A quick Google search reveals

Intel's Short Vector Math Library (SVML).

It seems that _mm_sin_ps is not actually an instruction that an

x86 CPU can run.

Rather the intrinsic is implemented as part of an Intel library.

We could have seen this in the

Intel intrinsics guide

where it is marked as sequence.

This meens that it does not correspond to a single CPU instruction but is

implemented as a sequence of instructions.

Manual Implementation

This leaves us with no other otion than to implement our own sin function.

I based my implementation on the

avx_mathfun repository on GitHub.

#include <immintrin.h>

__m256 mm256_sincos_ps(__m256 x, __m256* c) {

__m256 signBitSin = x;

// Take the absolute value

__m256 invSignMask = _mm256_castsi256_ps(_mm256_set1_epi32((int)~0x80000000));

x = _mm256_and_ps(x, invSignMask);

// Extract the sign bit (most significant bit)

__m256 signMask = _mm256_castsi256_ps(_mm256_set1_epi32(0x80000000));

signBitSin = _mm256_and_ps(signBitSin, signMask);

// Scale by (4 / PI)

__m256 fourDivPi = _mm256_set1_ps(1.27323954473516f);

__m256 y = _mm256_mul_ps(x, fourDivPi);

// Store the integer part of y in imm2

__m256i imm2 = _mm256_cvttps_epi32(y);

// j = (j+1) & (~1)

imm2 = _mm256_add_epi32(imm2, _mm256_set1_epi32(1));

imm2 = _mm256_and_si256(imm2, _mm256_set1_epi32(~1));

y = _mm256_cvtepi32_ps(imm2);

__m256i imm4 = imm2;

// Get the swap sign flag for the sine

__m256i imm0 = _mm256_and_si256(imm2, _mm256_set1_epi32(4));

imm0 = _mm256_slli_epi32(imm0, 29);

__m256 swapSignBitSin = _mm256_castsi256_ps(imm0);

// Get the polynom selection mask for the sine

imm2 = _mm256_and_si256(imm2, _mm256_set1_epi32(2));

imm2 = _mm256_cmpeq_epi32(imm2, _mm256_set1_epi32(0));

__m256 polynomMask = _mm256_castsi256_ps(imm2);

// The magic pass: "Extended precision modular arithmetic"

// x = ((x - y * DP1) - y * DP2) - y * DP3;

__m256 xmm1 = _mm256_set1_ps(-0.78515625f); // DP1

__m256 xmm2 = _mm256_set1_ps(-2.4187564849853515625e-4); // DP2

__m256 xmm3 = _mm256_set1_ps(-3.77489497744594108e-8); // DP3

xmm1 = _mm256_mul_ps(y, xmm1);

xmm2 = _mm256_mul_ps(y, xmm2);

xmm3 = _mm256_mul_ps(y, xmm3);

x = _mm256_add_ps(x, xmm1);

x = _mm256_add_ps(x, xmm2);

x = _mm256_add_ps(x, xmm3);

imm4 = _mm256_sub_epi32(imm4, _mm256_set1_epi32(2));

imm4 = _mm256_andnot_si256(imm4, _mm256_set1_epi32(4));

imm4 = _mm256_slli_epi32(imm4, 29);

__m256 signBitCos = _mm256_castsi256_ps(imm4);

signBitSin = _mm256_xor_ps(signBitSin, swapSignBitSin);

// Evaluate the first polynom (0 <= x <= Pi/4)

__m256 z = _mm256_mul_ps(x, x);

y = _mm256_set1_ps(2.443315711809948E-005f); // cos coefficient p0

y = _mm256_mul_ps(y, z);

y = _mm256_add_ps(y, _mm256_set1_ps(-1.388731625493765E-003f)); // cos coefficient p1

y = _mm256_mul_ps(y, z);

y = _mm256_add_ps(y, _mm256_set1_ps(4.166664568298827E-002f)); // cos coefficient p2

y = _mm256_mul_ps(y, z);

y = _mm256_mul_ps(y, z);

__m256 tmp = _mm256_mul_ps(z, _mm256_set1_ps(0.5f));

y = _mm256_sub_ps(y, tmp);

y = _mm256_add_ps(y, _mm256_set1_ps(1));

// Evaluate the second polynom (Pi/4 <= x <= 0)

__m256 y2 = _mm256_set1_ps(-1.9515295891E-4f); // sin coefficient p0

y2 = _mm256_mul_ps(y2, z);

y2 = _mm256_add_ps(y2, _mm256_set1_ps(8.3321608736E-3f)); // sin coefficient p1

y2 = _mm256_mul_ps(y2, z);

y2 = _mm256_add_ps(y2, _mm256_set1_ps(-1.6666654611E-1f)); // sin coefficient p2

y2 = _mm256_mul_ps(y2, z);

y2 = _mm256_mul_ps(y2, x);

y2 = _mm256_add_ps(y2, x);

// Select the correct result from the two polynoms

xmm3 = polynomMask;

__m256 ysin2 = _mm256_and_ps(xmm3, y2);

__m256 ysin1 = _mm256_andnot_ps(xmm3, y);

y2 = _mm256_sub_ps(y2, ysin2);

y = _mm256_sub_ps(y, ysin1);

xmm1 = _mm256_add_ps(ysin1, ysin2);

xmm2 = _mm256_add_ps(y, y2);

// Update the sign

*c = _mm256_xor_ps(xmm2, signBitCos);

return _mm256_xor_ps(xmm1, signBitSin);

}

float sin(float x) {

__m256 x8 = _mm256_set1_ps(x);

__m256 ignore;

__m256 sin8 = mm256_sincos_ps(x8, &ignore);

return *(float*)&sin8;

}

Sine in Action

We now have our own implementation for sine and cosine. I was hoping that it might be a bit easier than a full-blown implementation from scratch. However, at the moment, I am satisfied with the result. Here you can see an animation where the brightness of the triangle oscillates over time using our sine function, not perfectly looped :)